This post originally appeared at the Legislation Law Prof Blog

Yesterday, Wisconsin governor and all-but-official presidential candidate Scott Walker signed a so-called “right to work” bill into law. It was published today. Wisconsin is now the 25th state with such a law. But interestingly, Walker was careful not to describe what he signed as a “right to work” law. From his quotes at the signing event to the sign taped to his desk to his press release, he instead called it a “Freedom to Work” law.

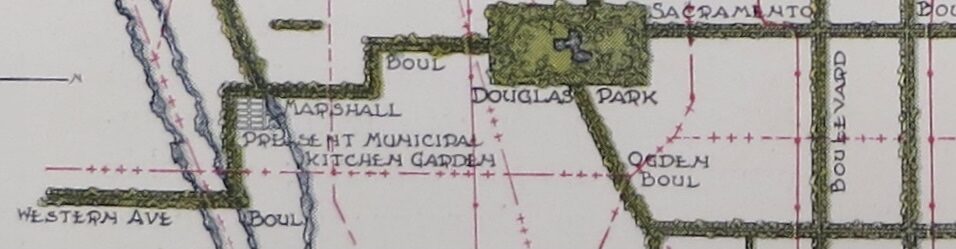

(Mike De Sisti/Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, via Associated Press)

This tweak was a bit odd, since Wisconsin’s Legislative Reference Bureau had summarized S.B. 44 by writing “This bill creates a state right to work law.” The term “right to work” also appeared in the text of the bill itself, and now in 2015 Wisconsin Act 1.

Why the difference? Why “freedom” rather than “right”?

It could be that Walker and his aides were simply looking for a better frame. Though it’s not clear what was wrong with “right to work” in the first place. “Right to work,” which no less a wonk than Ezra Klein has called “a triumph of framing,” has put opponents on the defensive, fumbling for alternatives such as “right to work for less,” or “so-called ‘right to work’” (see above), or even “right to freeload.”

Perhaps instead — who can really say? — the change was because Walker doesn’t want to foster the impression that his law actually creates a right to work. It doesn’t, of course, not any more than it creates a duty to provide employment. (More tomorrow, in Part 2, on ideas of what that — an actual right to work — might look like.)

If this is the real reason behind Walker’s reframing — and admittedly, it’s probably not — then he might be commended for trying to get things at least a little closer to the truth. We might think of “freedom to work” as an almost-truth, a little bit of Walkerian truthiness.

Why does it get closer to the truth? Here we must summon the ghost of Wesley Hohfeld, who just over a century ago wrote in the Yale Law Journal that “the term ‘rights’ tends to be used indiscriminately to cover what in a given case may be a privilege, a power, or an immunity, rather than a right in the strictest sense; and this looseness of usage is occasionally recognized by the authorities.”

Hohfeld famously (at least among legal scholars) took it upon himself to clear things up, by laying out a scheme of fundamental jural relations:

In Hohfeld’s terminology, jural correlatives are legal relations in which one thing corresponds to another. For example, if X has a right against Y to receive employment, the correlative is that Y is under a duty toward X to provide employment. Obviously, this sort of right-duty relation is not what is at stake in “right to work” laws.

Instead, Walker’s reframing moves us over one column in Hohfeld’s table of jural correlatives. Hohfeld noted that “a privlege is the opposite of a duty, and the correlative of a ‘no-right.’” Here, if we think of Walker’s “freedom” as equivalent to Hohfeld’s “privilege” then at least Walker has identified, probably unknowingly, the correct jural relation in play. As Hohfeld put it, “A ‘liberty’ considered as a legal relation (or ‘right’ in the loose and generic sense of that term) must mean, if it have any definite content at all, precisely the same thing as privilege.”

So the law Walker signed gives workers a legal privilege — not to work per se (they already had that privilege), but to work without having to join a union or pay dues. This is the jural opposite of the duty that collective bargaining agreements could have created for workers as recently as last week. Then, a collective bargaining agreement could have created a duty on the part of a worker to pay the equivalent of dues. Not so anymore. After today, agreements renewed, modified, or extended may not create such a duty.

The correlative to the new legal privilege created by Walker’s “freedom to work” law is a no-right on the part of any person to compel a worker to join a union or pay the equivalent of dues as a condition of employment. What’s more, the law criminalizes the violation of this no-right. This is to say that any bosses (union or actual) who assert a right to compel union dues or membership not only don’t have that right, but have also committed a Class A misdemeanor. This criminal liability provision, of all things, is what falls under the title “Right to Work” in Section 12 of the Act.

In the end, then, putting “so-called” in front of “Right to Work” is conceptually correct. As Walker seems to have acknowledged, the law doesn’t create a right to work — it creates a freedom, or legal privilege, to work without having to pay dues or join a union. Put differently, it creates a legal privilege to free-ride on the agreements that unions have negotiated with employers.

Tomorrow, Part 2 will take a look at some visions people have had of a real right to work — and how their proposals have played out. And, later in the week, Part 3 will survey legislative proposals for the labor movement, now that workers in half the states have a legal privilege to free-ride.