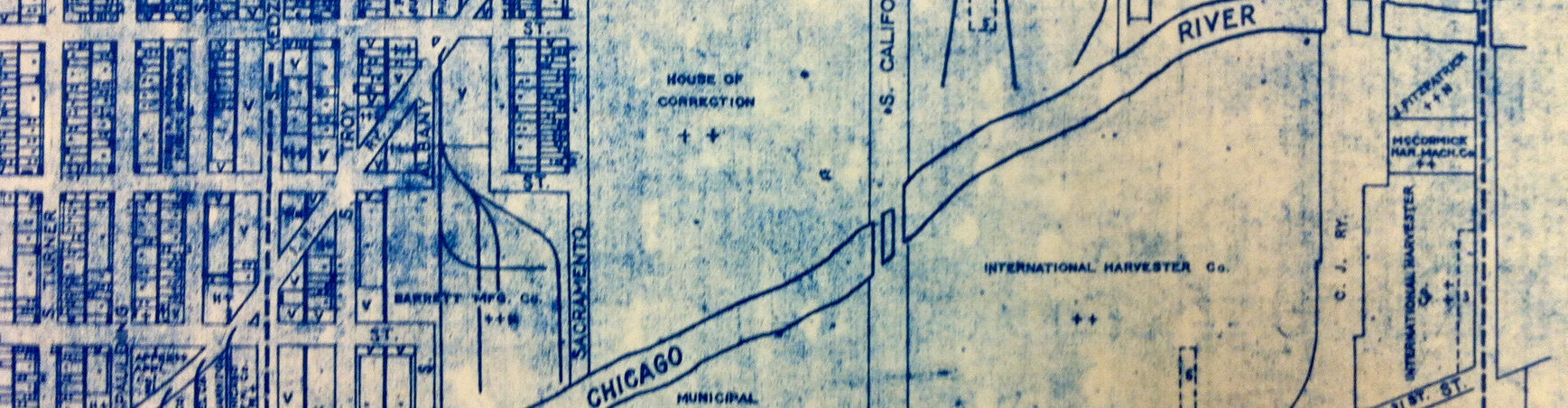

105 years ago today, Chicagoans opened the Daily Tribune and found out that their city would soon be the site of the largest urban farm in the United States. “Poor of City Get 90 Acres to Till,” announced the headline on page seven. The International Harvester company, a fabricator of agricultural implements run by Chicago’s McCormick family, had offered up the land for use as vegetable gardens. This was a boon for the City Gardens Association. The leaders of this new organization had been expecting to use vacant lots, at least until C.W. Price, the head of Harvester’s welfare department, recommended that they be given access to the company’s land.

This story from over a century ago is similar, at least in certain respects, to some recent reports about urban farming in Chicago. Just last year, Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced the city would open up acres of city-owned land for urban farming business incubators, in “one of first programs of its kind in the nation.” 2013 also saw the opening, just outside Chicago’s city limits, of “the largest vertical farm in the country.” People are once again trying to figure out how and where to fit farming into the urban landscape.

This spring and summer, I’m going to be blogging a bit about what urban farming was like in Chicago 100 years or so ago, with a focus on understanding and explaining the cooperative project between International Harvester and the City Gardens Association that was announced 105 years ago today. My aim is to start shedding some light on corners of Chicago’s history that have largely been forgotten, and to start sharing what I’ve been learning about how Chicago’s physical and social landscapes have changed over time.

My hope is also that the stories I’m digging up will be of interest to people who want to better understand how and why Chicago’s landscape is changing again – and, more generally, the social processes that drive change in urban landscapes. Mark Twain is sometimes quoted (probably incorrectly) as having said that “history never repeats itself, but it does rhyme.” I’m not suggesting here that we’re seeing the repeating turning and returning of a cyclical historical process as periods of urban farming come and go. But I do think that we can learn something about how and why urban landscapes have changed, and continue to change, by comparing how the various moments when urban farming has blossomed do (or don’t) rhyme.

In the posts to come, I’ll be asking how it was that in 1909 the City Gardens Association came to be looking for land, and why Harvester decided to provide it. I’ll also look into what people did with that land, and how people talked about the effects that access to a small patch of land had on gardeners. And more, as I think of it… Stay tuned!